One of Lisbon’s most iconic viewpoints, not even the 1755 earthquake could destroy this majestic point of entry into the capital of Portugal. The royal palace disappeared forever, but the public square retained its shape during reconstruction… although sporting a new name. Recently the columns returned with “Salazar” cleaned up for all to see. That polemic decision allows visitors & residents alike to engage in a dialogue with Portugal’s recent history.

Prior to the destruction of the waterfront in 1755, the Terreiro do Paço –the backyard of the royal palace– had been surrounded by shipyards as well as the Casa da Índia that controlled the empire’s international trade. One of my favorite pre-earthquake renditions of the square hangs on a wall of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga at the top of the first staircase. The oil painting shows the arrival of Felipe III of Spain in 1613 to a territory acquired by his father: Portugal. That’s another story for another time, but check out how astonished his court must have felt. No columns yet, but the importance of this location had been clearly established:

The earthquake-fire-tsunami of 1755 gave the Marquês de Pombal a blank slate to work with. I’ve always been impressed by those Enlightenment ideas that gave birth to the Baixa, but he also maintained symbolic respect of that large, open space along the banks of the Rio Tejo. Renamed Praça do Comércio since the palace reference no longer applied, these two names continue to confuse tourists today. The new quay (cais in Portuguese) is clearly visible on a 1785 city plan (just below “Z”):

Columns can be seen on engravings from the 1790s, but no record remains of when the first ones were placed on the waterfront. In 1809, a local newspaper referred to the area as the Caes das Columnas so surely lisboetas were calling it that some time before. The dock provided a quick drop-off for small goods as well as an entry to the city. Quite the hub of activity:

Spheres topped the columns in 1848, even as their design changed over the following decades. During the reign of King Carlos I, officials began to realize the impact of arrival to Lisbon here & used the columns for dramatic effect. Some heads-of-state to arrive at this dock were King Edward VII (UK · 1903), King Alfonso XIII (Spain · 1903), President Loubet (France · 1905), Emperor Wilhelm II (Germany · 1905) & a military attaché (Japan · 1907):

Governments came & went in early 20th-century Portugal, but the dramatic effect of the columns persisted & even declared part of the nation’s fledgling heritage organisation in 1910. Salazar took advantage of their presence to connect Lisbon to two overseas visits of Portugal’s world empire in the 1930s, leaving an engraving for all to see. In effect, the columns became a physical marker connecting Portugal to all the territory it controlled beyond. No translation needed to get a sense of the pomp & praise for these voyages:

SEGUNDA VIAGEM DO CHEFE DE ESTADO ÀS TERRAS ULTRAMARINAS

DO IMPÉRIO: CABO VERDE, MOÇAMBIQUE E ANGOLA.

XVII DE JUNHO – XII DE SETEMBRO DE MCMXXXIX

“A VIAGEM DO CHEFE DE ESTADO ÀS TERRAS DO IMPÉRIO EM ÁFRICA ESTÁ NA MESMA DIRECTRIZ DAS NOSSAS PREOCUPAÇÕES E FINALIDADE. É MANIFESTAÇÃO DO MESMO ESPÍRITO QUE PÔS DE PÉ O ACTO COLONIAL” SALAZAR

AQUI EMBARCOU O CHEFE DE ESTADO PARA A PRIMEIRA VIAGEM ÀS TERRAS ULTRAMARINAS DO IMPÉRIO: S. TOMÉ E PRÍNCIPE E ANGOLA XI DE JULHO – XII DE AGOSTO DE MCMXXXVIII

“COM CERTEZA DE QUE FALA PELA MINHA VOZ PORTUGAL INTEIRO, PROCLAMA A UNIDADE INDESTRUTÍVEL E ETERNA DE PORTUGAL, DE AQUÉM E DE ALÉM MAR”

GENERAL CARMONA

The columns witnessed a couple of important events after being engraved: the arrival of Queen Elizabeth II & the end of the dictatorship. In 1957, Her Royal Highness ended a world tour & reunited with her husband Prince Philip in Lisbon. News crews captured the disembarkment from the royal barge. In 1974, a peaceful military coup ended 41 years of dictatorship by the Estado Novo. Naval troops loyal to the establishment had been ordered to fire on the rebellion occupying Praça do Comércio. Fortunately they refused, but gunships framed by columns are a haunting image of what might have happened:

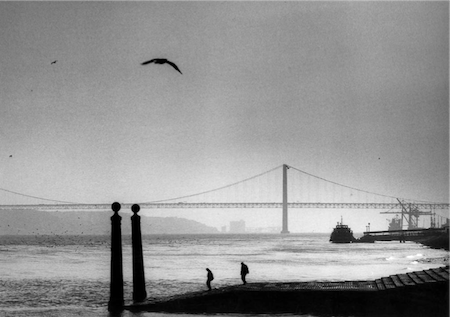

Affected by decades of corrosion, both columns were dismantled in 1996-97. Restoration works in Europe at the time called for minimal intervention so no immediate replacement was made. As the columns were cleaned offsite, Lisbon took advantage of a Metro line extension to reinforce the quay itself. Returned in 2008, most tourists these days never take time to decipher the text. A mini-beach attracts a crowd more interested in Instagram likes than national heritage… but an odd side-effect of those photos is maintaining the columns as protagonists in national history. Seems like every generation with a camera has been attracted to this location, including yours truly:

The tidal nature of the Rio Tejo in Lisbon provides a changing backdrop for two simple, stone columns that have seen just as many changes in national history. I’ll get flack for the following statement, but I applaud the decision to restore & replace the columns exactly as they were from the 1930s. I’ve met historians who feel like any physical remnant of a difficult past in plain sight is an affront to liberty & democracy. However, I think it goes beyond that. Their original use to honor a dictatorship can be transformed; remnants from the past can be used as a tool to teach & learn.

Ah, and unfortunately off limits at the moment due to the coronavirus pandemic: